Vanderbilt Open Streets

Q. how might we reveal the layers of experience and values in a transient New York City public space?

tl;dr

Open streets is an initiative in New York borne out of the pandemic that temporarily closes major arteries in neighborhoods across the city for pedestrian and bike use. Along with sidewalk restaurants, both these public space ideas came from a necessity of open air interaction and community gathering during some of the most challenging years in recent time.

As designers and researchers, a few local friends and I developed a fascination with Vanderbilt Ave, the street I live on, and its open street program.

When closed to cars, the street transforms into re-imagined worlds, teleporting people to a myriad of spaces, a curb to a beach, a shaded bench to a green oasis and outdoor seating to an Italian piazza.

Out of pure curiosity, we banded together to create a series of research exercises to better understand this complex environment that is always in flux, and maybe tease out questions about what it means to reclaim public space in the city.

-

42 interviews, 15 hours of observation, recording, drawing and mapping

-

Daniel Villegas, Karolina Piorko

-

As project lead, I organized weekly meetings and workshops for the team by assigning reading and research exercises. For field research, I was lead interviewer. All images are my own unless noted otherwise.

Creating a picture

[ quotes in black are from the 40 pedestrians we interviewed ]

[ quotes in pink are comments from the research team ]

[ my apartment!]

[ the fire hydrant’s on! ]

[ We asked people, stickers in hand, where do they feel…]

[ Open Streets is always popping, people are drawn to the space ]

[I like the novelty of hanging out on a street]

[ everyone’s together on the street but its like they’re all in their own bubbles ]

[ You know, this was pandemic thing and back then Vanderbilt was filled with magical moments of people that never got together or interacted, for protests, this idea of true civic engagement. Maybe people are tired now and open streets is more commercial ]

[ There’s food here, furniture, shade, I live right around the corner, it is very convenient ]

[ Its very hot, shade is like the most important resource ]

[ Green energy salesman says to us, looking at our clipboards, oh you guys are doing something too today, this neighborhood is the perfect demographic for us ]

[ Rules? There are no rules to occupy this space, do whatever you want ]

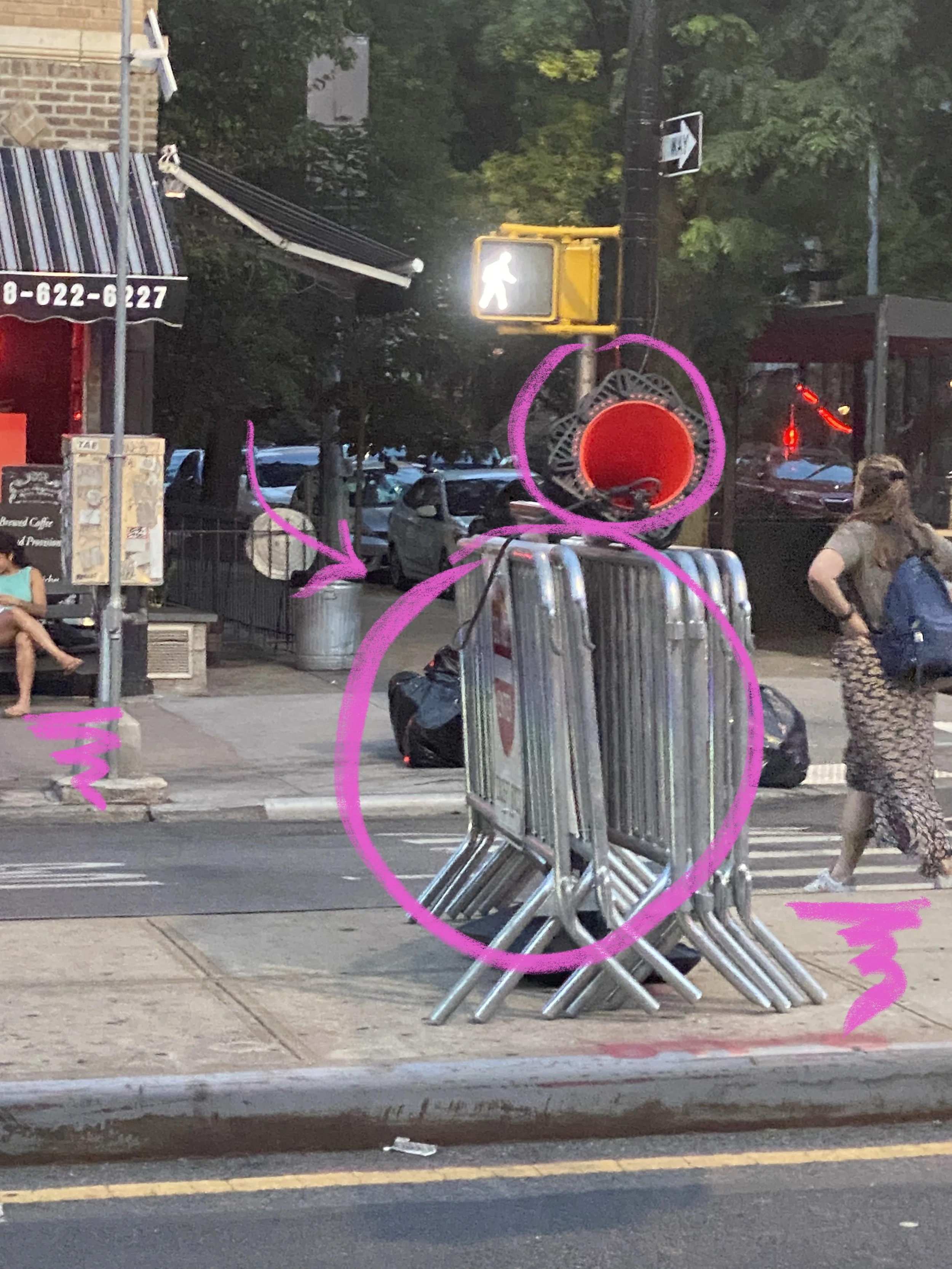

[ This part of the street is just empty, a wasteland closed off ]

[ we approached a woman working for doordash but we made her uncomfortable, asking her questions at what is her place of work ]

[ the median is special, my favorite place to sit ]

[ why did you choose here to sit? ]

[ I just really liked this brick ]

[ the bike lane switches sides each weekend to give the restaurants fair access to undisturbed public seating frontage ]

[ you know the guy who always plays music in that corner? yeah I don’t know anything about him but he always plays jams. Michael Jackson? oh yeah it’s a party ]

[ I get my laundry done, while I have my coffee and a bagel, sitting outside and catching up on work ]

[ credit: amNew York ]

[ I also triangulate, right there’s the bar, the wine store and Brooklyn Homeslice, pointing from his table ]

[ the community board stopped letting us barbeque. I’ve lived here for 40 years, it’s my block ]

[ I don’t volunteer I get paid to set up the barriers. It’s great except when I get cussed out by the drivers. Bikers and pedestrians love it. Have you noticed how there are no cops here? it’s a good neighborhood, if this was where I lived, man, we’d have cops every corner ]

[ where do I feel unsafe? Look at the delivery workers over there, they’re loud, noisy and I always think I will get run over ]

Carless New York?

Did we see a future of a more pedestrianized New York’s in Vanderbilt Ave’s open street program? Possibly. It is undeniable to see the benefits of open streets for a neighborhood. The energy, joy and freedom people seem to show in interviews and in observation is palpable.

However, the research also revealed strains of inequity and failings of infrastructure that are all barriers to transforming the neighborhood into a pedestrian haven, despite the absence of cars. In a space that is ‘un-designed’ for the type of use open streets demands, a few questions arise in terms of what interventions could be possible to make Vanderbilt the equitable, habitable space it could become.

The biggest conflict that our research revealed was the undercurrent of tension between pedestrians who now claim ownership of the street and the network of delivery drivers on motorcycles that rely on Vanderbilt for employment. Each group avoids the other, though both depend on each other and on the resources of public space for respite. The delivery drivers are seen as outsiders even though they stitch neighborhoods together and are one of the main reasons why businesses on Vanderbilt are flourishing.

With the recent passing of the couriers’ rights bill in New York, allowing workers to use bathrooms, what more could be designed during open streets to carve out space for delivery workers, finding belonging?

Another issue, unsurprisingly, is trash. Trash on the roads, the benches, in trash cans, most likely out of trash cans… Trash is the only thing that can compete with traffic cones in terms of ubiquity in the space. The lack of cleanliness reveals a strange relationship between the street and who might be responsible for it when no cars are occupying it.

On Vanderbilt, public and private realms are blended together, undulating in flexible boundaries around stoops, outdoor seating, restaurants and bike lanes. If Open streets is neither wholly public or private, who is responsible for maintenance such as cleanliness? Some claim the community board is or the department of sanitation, but others are very against being told what to do as they consider the street their private backyard.

The research involved a review of literature about public space and we found that very few models could accurately described open streets as they all depended on permanence and ownership.

One model however, seemed very apt: loose versus tight public spaces. Loose space freely invites occupants to participate diverse activities that they may not do so in more regulated, ‘designed’ spaces in the city such as barbecuing, large parties, graffiti, lying down on the asphalt etc. Interviewees were mostly unanimous in the idea that were no explicit rules to occupying Vanderbilt, revealing its sheer adaptability as public space.

If the neighborhood were to be more permanently pedestrianized, would Vanderbilt remain the interstitial, amorphous space that is given meaning by whomever occupies it or would permanence bring regulation? All these questions will form the basis of next year’s research project when open streets begins once more.

Literature review

Flaneur exercise

A flaneur is a “stroller", "lounger" or "saunterer", observing the environment around them. Our flaneur exercise to observe Vanderbilt consisted of sound recordings, photography and drawing.

Mapping

walking paths

seating types

traffic cones

green cover

1 , 2, 3 spaces

To fully document our observations, we kept a running log on maps of the street, block by block.

Survey design

The survey consisted of 8 questions, to take up to 3 minutes of time. We approached 52 people and successfully interviewed 41.